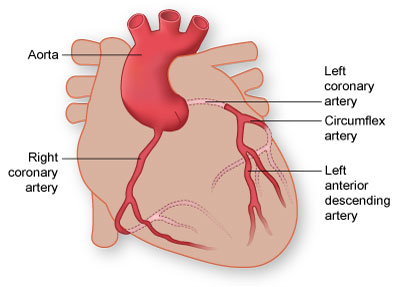

The Coronary Arteries:

Coronary Circulation

The heart muscle, like every other organ or tissue in your body, needs oxygen-rich blood to survive. Blood is supplied to the heart by its own vascular system, called coronary circulation.

The aorta (the main blood supplier to the body) branches off into two main coronary blood vessels (also called arteries). These coronary arteries branch off into smaller arteries, which supply oxygen-rich blood to the entire heart muscle.

The right coronary artery supplies blood mainly to the right side of the heart. The right side of the heart is smaller because it pumps blood only to the lungs.

The left coronary artery, which branches into the left anterior descending artery and the circumflex artery, supplies blood to the left side of the heart. The left side of the heart is larger and more muscular because it pumps blood to the rest of the body.

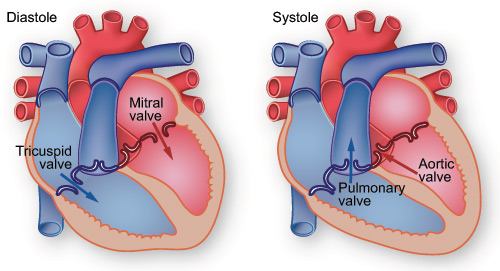

The Heart Valves:

Four valves regulate blood flow through your heart:

* The tricuspid valve regulates blood flow between the right atrium and right ventricle.

* The pulmonary valve controls blood flow from the right ventricle into the pulmonary arteries, which carry blood to your lungs to pick up oxygen.

* The mitral valve lets oxygen-rich blood from your lungs pass from the left atrium into the left ventricle.

* The aortic valve opens the way for oxygen-rich blood to pass from the left ventricle into the aorta, your body's largest artery, where it is delivered to the rest of the body.

The Heartbeat:

A heartbeat is a two-part pumping action that takes about a second. As blood collects in the upper chambers (the right and left atria), the heart's natural pacemaker (the SA node) sends out an electrical signal that causes the atria to contract. This contraction pushes blood through the tricuspid and mitral valves into the resting lower chambers (the right and left ventricles). This part of the two-part pumping phase (the longer of the two) is called diastole.

The second part of the pumping phase begins when the ventricles are full of blood. The electrical signals from the SA node travel along a pathway of cells to the ventricles, causing them to contract. This is called systole. As the tricuspid and mitral valves shut tight to prevent a back flow of blood, the pulmonary and aortic valves are pushed open. While blood is pushed from the right ventricle into the lungs to pick up oxygen, oxygen-rich blood flows from the left ventricle to the heart and other parts of the body.

After blood moves into the pulmonary artery and the aorta, the ventricles relax, and the pulmonary and aortic valves close. The lower pressure in the ventricles causes the tricuspid and mitral valves to open, and the cycle begins again. This series of contractions is repeated over and over again, increasing during times of exertion and decreasing while you are at rest. The heart normally beats about 60 to 80 times a minute when you are at rest, but this can vary. As you get older, your resting heart rate rises. Also, it is usually lower in people who are physically fit.

Your heart does not work alone, though. Your brain tracks the conditions around you—climate, stress, and level of physical activity—and adjusts your cardiovascular system to meet those needs.

The human heart is a muscle designed to remain strong and reliable for a hundred years or longer. By reducing your risk factors for cardiovascular disease, you may help your heart stay healthy longer.

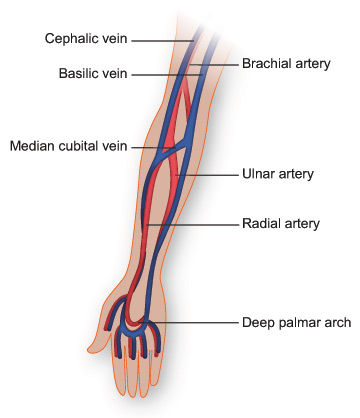

Vasculature of the Arm:

The one-way circulatory system carries blood to all parts of your body. This process of blood flow within your body is called circulation. Arteries carry oxygen-rich blood away from your heart, and veins carry oxygen-poor blood back to your heart.

In pulmonary circulation, though, the roles are switched. It is the pulmonary artery that brings oxygen-poor blood into your lungs and the pulmonary vein that brings oxygen-rich blood back to your heart.

In the diagram, the vessels that carry oxygen-rich blood are colored red, and the vessels that carry oxygen-poor blood are colored blue.

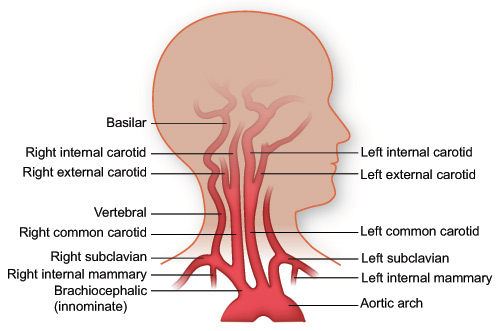

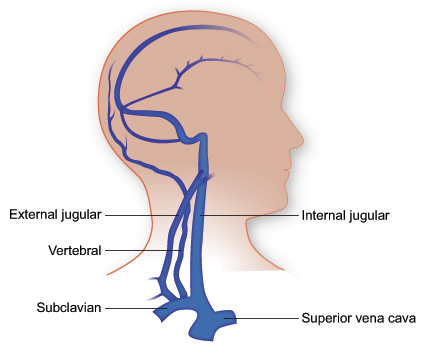

Vasculature of the Head:

The one-way circulatory system carries blood to all parts of your body. This process of blood flow within your body is called circulation. Arteries carry oxygen-rich blood away from your heart, and veins carry oxygen-poor blood back to your heart.

In pulmonary circulation, though, the roles are switched. It is the pulmonary artery that brings oxygen-poor blood into your lungs and the pulmonary vein that brings oxygen-rich blood back to your heart.

In the diagrams, the vessels that carry oxygen-rich blood are colored red, and the vessels that carry oxygen-poor blood are colored blue.

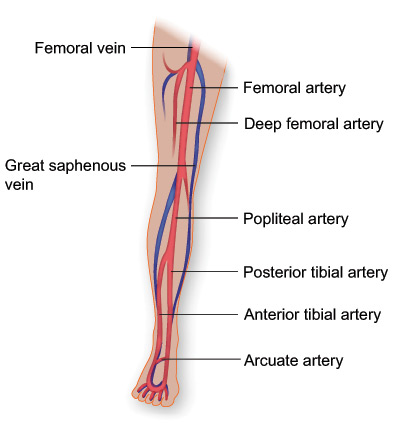

Vasculature of the Leg:

The one-way circulatory system carries blood to all parts of your body. This process of blood flow within your body is called circulation. Arteries carry oxygen-rich blood away from your heart, and veins carry oxygen-poor blood back to your heart.

In pulmonary circulation, though, the roles are switched. It is the pulmonary artery that brings oxygen-poor blood into your lungs and the pulmonary vein that brings oxygen-rich blood back to your heart.

In the diagram, the vessels that carry oxygen-rich blood are colored red, and the vessels that carry oxygen-poor blood are colored blue.

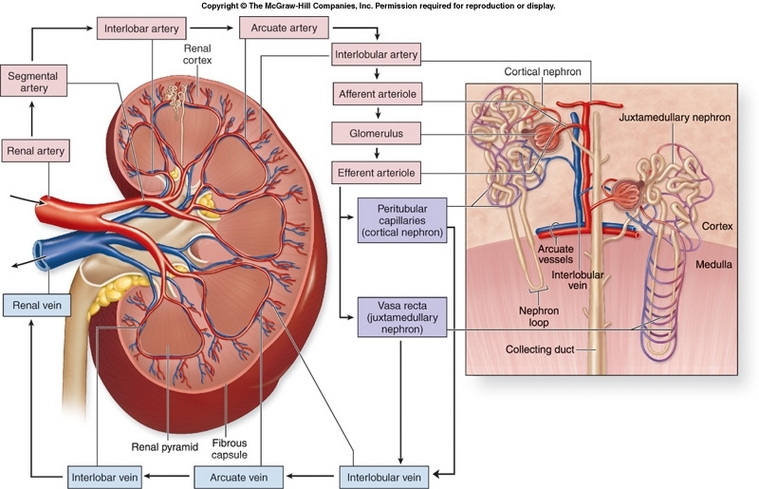

everything about kidney!

The Kidneys and How They Work

The kidneys are a pair of vital organs that perform many functions to keep the blood clean and chemically balanced. Understanding how the kidneys work can help a person keep them healthy.

What do the kidneys do?

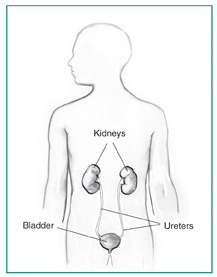

The kidneys are bean-shaped organs, each about the size of a fist. They are located near the middle of the back, just below the rib cage, one on each side of the spine. The kidneys are sophisticated reprocessing machines. Every day, a person’s kidneys process about 200 quarts of blood to sift out about 2 quarts of waste products and extra water. The wastes and extra water become urine, which flows to the bladder through tubes called ureters. The bladder stores urine until releasing it through urination.

Drawing of the urinary tract in a male figure with labels for the kidneys, bladder, and ureters.

The kidneys remove wastes and water from the blood to form urine. Urine flows from the kidneys to the bladder through the ureters.

Wastes in the blood come from the normal breakdown of active tissues, such as muscles, and from food. The body uses food for energy and self-repairs. After the body has taken what it needs from food, wastes are sent to the blood. If the kidneys did not remove them, these wastes would build up in the blood and damage the body.

The actual removal of wastes occurs in tiny units inside the kidneys called nephrons. Each kidney has about a million nephrons. In the nephron, a glomerulus—which is a tiny blood vessel, or capillary—intertwines with a tiny urine-collecting tube called a tubule. The glomerulus acts as a filtering unit, or sieve, and keeps normal proteins and cells in the bloodstream, allowing extra fluid and wastes to pass through. A complicated chemical exchange takes place, as waste materials and water leave the blood and enter the urinary system.

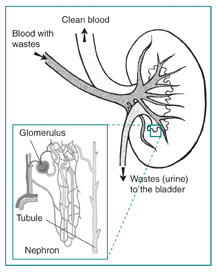

Drawing of a kidney. Labels show where blood with wastes enter the kidney, clean blood leaves the kidney, and wastes (urine) are sent to the bladder. An inset shows a microscopic view of a nephron. Labels point to the glomerulus and the tubule.

In the nephron (left), tiny blood vessels intertwine with urine-collecting tubes. Each kidney contains about 1 million nephrons.

At first, the tubules receive a combination of waste materials and chemicals the body can still use. The kidneys measure out chemicals like sodium, phosphorus, and potassium and release them back to the blood to return to the body. In this way, the kidneys regulate the body’s level of these substances. The right balance is necessary for life.

In addition to removing wastes, the kidneys release three important hormones:

* erythropoietin, or EPO, which stimulates the bone marrow to make red blood cells

* renin, which regulates blood pressure

* calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D, which helps maintain calcium for bones and for normal chemical balance in the body

What is renal function?

The word “renal” refers to the kidneys. The terms “renal function” and “kidney function” mean the same thing. Health professionals use the term “renal function” to talk about how efficiently the kidneys filter blood. People with two healthy kidneys have 100 percent of their kidney function. Small or mild declines in kidney function—as much as 30 to 40 percent—would rarely be noticeable. Kidney function is now calculated using a blood sample and a formula to find the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). The eGFR corresponds to the percent of kidney function available. The section “What medical tests detect kidney disease?” contains more details about the eGFR.

Some people are born with only one kidney but can still lead normal, healthy lives. Every year, thousands of people donate one of their kidneys for transplantation to a family member or friend.

For many people with reduced kidney function, a kidney disease is also present and will get worse. Serious health problems occur when people have less than 25 percent of their kidney function. When kidney function drops below 10 to 15 percent, a person needs some form of renal replacement therapy—either blood-cleansing treatments called dialysis or a kidney transplant—to sustain life.

Why do kidneys fail?

Most kidney diseases attack the nephrons, causing them to lose their filtering capacity. Damage to the nephrons can happen quickly, often as the result of injury or poisoning. But most kidney diseases destroy the nephrons slowly and silently. Only after years or even decades will the damage become apparent. Most kidney diseases attack both kidneys simultaneously.

The two most common causes of kidney disease are diabetes and high blood pressure. People with a family history of any kind of kidney problem are also at risk for kidney disease.

Diabetic Kidney Disease

Diabetes is a disease that keeps the body from using glucose, a form of sugar, as it should. If glucose stays in the blood instead of breaking down, it can act like a poison. Damage to the nephrons from unused glucose in the blood is called diabetic kidney disease. Keeping blood glucose levels down can delay or prevent diabetic kidney disease. Use of medications called angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) to treat high blood pressure can also slow or delay the progression of diabetic kidney disease.

High Blood Pressure

High blood pressure can damage the small blood vessels in the kidneys. The damaged vessels cannot filter wastes from the blood as they are supposed to.

A doctor may prescribe blood pressure medication. ACE inhibitors and ARBs have been found to protect the kidneys even more than other medicines that lower blood pressure to similar levels. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), one of the National Institutes of Health, recommends that people with diabetes or reduced kidney function keep their blood pressure below 130/80.

Glomerular Diseases

Several types of kidney disease are grouped together under this category, including autoimmune diseases, infection-related diseases, and sclerotic diseases. As the name indicates, glomerular diseases attack the tiny blood vessels, or glomeruli, within the kidney. The most common primary glomerular diseases include membranous nephropathy, IgA nephropathy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. The first sign of a glomerular disease is often proteinuria, which is too much protein in the urine. Another common sign is hematuria, which is blood in the urine. Some people may have both proteinuria and hematuria. Glomerular diseases can slowly destroy kidney function. Blood pressure control is important with any kidney disease. Glomerular diseases are usually diagnosed with a biopsy—a procedure that involves taking a piece of kidney tissue for examination with a microscope. Treatments for glomerular diseases may include immunosuppressive drugs or steroids to reduce inflammation and proteinuria, depending on the specific disease.

Inherited and Congenital Kidney Diseases

Some kidney diseases result from hereditary factors. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD), for example, is a genetic disorder in which many cysts grow in the kidneys. PKD cysts can slowly replace much of the mass of the kidneys, reducing kidney function and leading to kidney failure.

Some kidney problems may show up when a child is still developing in the womb. Examples include autosomal recessive PKD, a rare form of PKD, and other developmental problems that interfere with the normal formation of the nephrons. The signs of kidney disease in children vary. A child may grow unusually slowly, vomit often, or have back or side pain. Some kidney diseases may be silent—causing no signs or symptoms—for months or even years.

If a child has a kidney disease, the child’s doctor should find it during a regular checkup. The first sign of a kidney problem may be high blood pressure; a low number of red blood cells, called anemia; proteinuria; or hematuria. If the doctor finds any of these problems, further tests may be necessary, including additional blood and urine tests or radiology studies. In some cases, the doctor may need to perform a biopsy.

Some hereditary kidney diseases may not be detected until adulthood. The most common form of PKD was once called “adult PKD” because the symptoms of high blood pressure and renal failure usually do not occur until patients are in their twenties or thirties. But with advances in diagnostic imaging technology, doctors have found cysts in children and adolescents before any symptoms appear.

Other Causes of Kidney Disease

Poisons and trauma, such as a direct and forceful blow to the kidneys, can lead to kidney disease.

Some over-the-counter medicines can be poisonous to the kidneys if taken regularly over a long period of time. Anyone who takes painkillers regularly should check with a doctor to make sure the kidneys are not at risk.

How do kidneys fail?

Many factors that influence the speed of kidney failure are not completely understood. Researchers are still studying how protein in the diet and cholesterol levels in the blood affect kidney function.

Acute Kidney Injury

Some kidney problems happen quickly, such as when an accident injures the kidneys. Losing a lot of blood can cause sudden kidney failure. Some drugs or poisons can make the kidneys stop working. These sudden drops in kidney function are called acute kidney injury (AKI). Some doctors may also refer to this condition as acute renal failure (ARF).

AKI may lead to permanent loss of kidney function. But if the kidneys are not seriously damaged, acute kidney disease may be reversed.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Most kidney problems, however, happen slowly. A person may have “silent” kidney disease for years. Gradual loss of kidney function is called chronic kidney disease (CKD) or chronic renal insufficiency. People with CKD may go on to develop permanent kidney failure. They also have a high risk of death from a stroke or heart attack.

End-stage Renal Disease

Total or nearly total and permanent kidney failure is called end-stage renal disease (ESRD). People with ESRD must undergo dialysis or transplantation to stay alive.

What are the signs of chronic kidney disease (CKD)?

People in the early stages of CKD usually do not feel sick at all.

People whose kidney disease has gotten worse may

* need to urinate more often or less often

* feel tired

* lose their appetite or experience nausea and vomiting

* have swelling in their hands or feet

* feel itchy or numb

* get drowsy or have trouble concentrating

* have darkened skin

* have muscle cramps

What medical tests detect kidney disease?

Because a person can have kidney disease without any symptoms, a doctor may first detect the condition through routine blood and urine tests. The National Kidney Foundation recommends three simple tests to screen for kidney disease: a blood pressure measurement, a spot check for protein or albumin in the urine, and a calculation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) based on a serum creatinine measurement. Measuring urea nitrogen in the blood provides additional information.

Blood Pressure Measurement

High blood pressure can lead to kidney disease. It can also be a sign that the kidneys are already impaired. The only way to know whether a person’s blood pressure is high is to have a health professional measure it with a blood pressure cuff. The result is expressed as two numbers. The top number, which is called the systolic pressure, represents the pressure in the blood vessels when the heart is beating. The bottom number, which is called the diastolic pressure, shows the pressure when the heart is resting between beats. A person’s blood pressure is considered normal if it stays below 120/80, stated as “120 over 80.” The NHLBI recommends that people with kidney disease use whatever therapy is necessary, including lifestyle changes and medicines, to keep their blood pressure below 130/80.

Microalbuminuria and Proteinuria

Healthy kidneys take wastes out of the blood but leave protein. Impaired kidneys may fail to separate a blood protein called albumin from the wastes. At first, only small amounts of albumin may leak into the urine, a condition known as microalbuminuria, a sign of deteriorating kidney function. As kidney function worsens, the amount of albumin and other proteins in the urine increases, and the condition is called proteinuria. A doctor may test for protein using a dipstick in a small sample of a person’s urine taken in the doctor’s office. The color of the dipstick indicates the presence or absence of proteinuria.

A more sensitive test for protein or albumin in the urine involves laboratory measurement and calculation of the protein-to-creatinine or albumin-to-creatinine ratio. Creatinine is a waste product in the blood created by the normal breakdown of muscle cells during activity. Healthy kidneys take creatinine out of the blood and put it into the urine to leave the body. When the kidneys are not working well, creatinine builds up in the blood.

The albumin-to-creatinine measurement should be used to detect kidney disease in people at high risk, especially those with diabetes or high blood pressure. If a person’s first laboratory test shows high levels of protein, another test should be done 1 to 2 weeks later. If the second test also shows high levels of protein, the person has persistent proteinuria and should have additional tests to evaluate kidney function.

Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) Based on Creatinine Measurement

GFR is a calculation of how efficiently the kidneys are filtering wastes from the blood. A traditional GFR calculation requires an injection into the bloodstream of a substance that is later measured in a 24-hour urine collection. Recently, scientists found they could calculate GFR without an injection or urine collection. The new calculation—the eGFR—requires only a measurement of the creatinine in a blood sample.

In a laboratory, a person’s blood is tested to see how many milligrams of creatinine are in one deciliter of blood (mg/dL). Creatinine levels in the blood can vary, and each laboratory has its own normal range, usually 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL. A person whose creatinine level is only slightly above this range will probably not feel sick, but the elevation is a sign that the kidneys are not working at full strength. One formula for estimating kidney function equates a creatinine level of 1.7 mg/dL for most men and 1.4 mg/dL for most women to 50 percent of normal kidney function. But because creatinine values are so variable and can be affected by diet, a GFR calculation is more accurate for determining whether a person has reduced kidney function.

The eGFR calculation uses the patient’s creatinine measurement along with age and values assigned for sex and race. Some medical laboratories may make the eGFR calculation when a creatinine value is measured and include it on the lab report. The National Kidney Foundation has determined different stages of CKD based on the value of the eGFR. Dialysis or transplantation is needed when the eGFR is less than 15 milliliters per minute (mL/min).

Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN)

Blood carries protein to cells throughout the body. After the cells use the protein, the remaining waste product is returned to the blood as urea, a compound that contains nitrogen. Healthy kidneys take urea out of the blood and put it in the urine. If a person’s kidneys are not working well, the urea will stay in the blood.

A deciliter of normal blood contains 7 to 20 milligrams of urea. If a person’s BUN is more than 20 mg/dL, the kidneys may not be working at full strength. Other possible causes of an elevated BUN include dehydration and heart failure.

Additional Tests for Kidney Disease

If blood and urine tests indicate reduced kidney function, a doctor may recommend additional tests to help identify the cause of the problem.

Kidney imaging. Methods of kidney imaging—taking pictures of the kidneys—include ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These tools are most helpful in finding unusual growths or blockages to the flow of urine.

Kidney biopsy. A doctor may want to examine a tiny piece of kidney tissue with a microscope. To obtain this tissue sample, the doctor will perform a kidney biopsy—a hospital procedure in which the doctor inserts a needle through the patient’s skin into the back of the kidney. The needle retrieves a strand of tissue less than an inch long. For the procedure, the patient lies facedown on a table and receives a local anesthetic to numb the skin. The sample tissue will help the doctor identify problems at the cellular level.

For more information, see the fact sheet Kidney Biopsy from the National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse.

What are the stages of CKD?

A person’s eGFR is the best indicator of how well the kidneys are working. An eGFR of 90 or above is considered normal. A person whose eGFR stays below 60 for 3 months or longer has CKD. As kidney function declines, the risk of complications rises.

Moderate decrease in eGFR (30 to 59). At this stage of CKD, hormones and minerals can be thrown out of balance, leading to anemia and weak bones. A health care provider can help prevent or treat these complications with medicines and advice about food choices.

Severe reduction in eGFR (15 to 29). The patient should continue following the treatment for complications of CKD and learn as much as possible about the treatments for kidney failure. Each treatment requires preparation. Those who choose hemodialysis will need to have a procedure to make veins in their arms larger and stronger for repeated needle insertions. For peritoneal dialysis, one will need to have a catheter placed in the abdomen. A catheter is a thin, flexible tube used to fill the abdominal cavity with fluid. A person may want to ask family or friends to consider donating a kidney for transplantation.

Kidney failure (eGFR less than 15). When the kidneys do not work well enough to maintain life, dialysis or a kidney transplant will be needed.

In addition to tracking eGFR, blood tests can show when substances in the blood are out of balance. If phosphorus or potassium levels start to climb, a blood test will prompt the health care provider to address these issues before they permanently affect the person’s health.

What can be done about CKD?

Unfortunately, CKD often cannot be cured. But people in the early stages of CKD may be able to make their kidneys last longer by taking certain steps. They will also want to minimize the risks for heart attack and stroke because CKD patients are susceptible to these problems.

* People with reduced kidney function should see their doctor regularly. The primary doctor may refer the patient to a nephrologist, a doctor who specializes in kidney disease.

* People who have diabetes should watch their blood glucose levels closely to keep them under control. They should ask their health care provider about the latest in treatment.

* People with reduced renal function should avoid pain pills that may make their kidney disease worse. They should check with their health care provider before taking any medicine.

Controlling Blood Pressure

People with reduced kidney function and high blood pressure should control their blood pressure with an ACE inhibitor or an ARB. Many people will require two or more types of medication to keep their blood pressure below 130/80. A diuretic is an important addition when the ACE inhibitor or ARB does not meet the blood pressure goal.

Changing the Diet

People with reduced kidney function need to be aware that some parts of a normal diet may speed their kidney failure.

Protein. Protein is important to the body. It helps the body repair muscles and fight disease. Protein comes mostly from meat but can also be found in eggs, milk, nuts, beans, and other foods. Healthy kidneys take wastes out of the blood but leave in the protein. Impaired kidneys may fail to separate the protein from the wastes.

Some doctors tell their kidney patients to limit the amount of protein they eat so the kidneys have less work to do. But a person cannot avoid protein entirely. People with CKD can work with a dietitian to create the right food plan.

Cholesterol. Another problem that may be associated with kidney failure is high cholesterol. High levels of cholesterol in the blood may result from a high-fat diet.

Cholesterol can build up on the inside walls of blood vessels. The buildup makes pumping blood through the vessels harder for the heart and can cause heart attacks and strokes.

Sodium. Sodium is a chemical found in salt and other foods. Sodium in the diet may raise a person’s blood pressure, so people with CKD should limit foods that contain high levels of sodium. High-sodium foods include canned or processed foods like frozen dinners and hot dogs.

Potassium. Potassium is a mineral found naturally in many fruits and vegetables, such as oranges, potatoes, bananas, dried fruits, dried beans and peas, and nuts. Healthy kidneys measure potassium in the blood and remove excess amounts. Diseased kidneys may fail to remove excess potassium. With very poor kidney function, high potassium levels can affect the heart rhythm.

Not Smoking

Smoking not only increases the risk of kidney disease, but it also contributes to deaths from strokes and heart attacks in people with CKD.

Treating Anemia

Anemia is a condition in which the blood does not contain enough red blood cells. These cells are important because they carry oxygen throughout the body. A person who is anemic will feel tired and look pale. Healthy kidneys make the hormone EPO, which stimulates the bones to make red blood cells. Diseased kidneys may not make enough EPO. A person with CKD may need to take injections of a form of EPO.

Preparing for End-stage Renal Disease (ESRD)

As kidney disease progresses, a person needs to make several decisions. People in the later stages of CKD need to learn about their options for treating the last stages of kidney failure so they can make an informed choice between hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and transplantation.

What happens if the kidneys fail completely?

Total or nearly total and permanent kidney failure is called ESRD. If a person’s kidneys stop working completely, the body fills with extra water and waste products. This condition is called uremia. Hands or feet may swell. A person will feel tired and weak because the body needs clean blood to function properly.

Untreated uremia may lead to seizures or coma and will ultimately result in death. A person whose kidneys stop working completely will need to undergo dialysis or kidney transplantation.

Dialysis

The two major forms of dialysis are hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Hemodialysis uses a special filter called a dialyzer that functions as an artificial kidney to clean a person’s blood. The dialyzer is a canister connected to the hemodialysis machine. During treatment, the blood travels through tubes into the dialyzer, which filters out wastes, extra salt, and extra water. Then the cleaned blood flows through another set of tubes back into the body. The hemodialysis machine monitors blood flow and removes wastes from the dialyzer. Hemodialysis is usually performed at a dialysis center three times per week for 3 to 4 hours. A small but growing number of clinics offer home hemodialysis in addition to standard in-clinic treatments. The patient first learns to do treatments at the clinic, working with a dialysis nurse. Daily home hemodialysis is done 5 to 7 days per week for 2 to 3 hours at a time. Nocturnal dialysis can be performed for 8 hours at night while a person sleeps. Research as to which is the best method for dialysis is under way, but preliminary data indicate that daily dialysis schedules such as short daily dialysis or nocturnal dialysis may be the best form of dialysis therapy.

Drawing of a man receiving hemodialysis treatment. Labels point to the hemodialyzer, where filtering takes place; hemodialysis machine; a tube where unfiltered blood flows to the dialyzer; and a tube where filtered blood flows back to the patient’s body.

Hemodialysis

In peritoneal dialysis, a fluid called dialysis solution is put into the abdomen. This fluid captures the waste products from a person’s blood. After a few hours when the fluid is nearly saturated with wastes, the fluid is drained through a catheter. Then, a fresh bag of fluid is dripped into the abdomen to continue the cleansing process. Patients can perform peritoneal dialysis themselves. Patients using continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) change fluid four times a day. Another form of peritoneal dialysis, called continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis (CCPD), can be performed at night with a machine that drains and refills the abdomen automatically.

Diagram of a patient receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Labels point to the dialysis solution, catheter, peritoneum, and abdominal cavity.

Peritoneal dialysis

Transplantation

A donated kidney may come from an anonymous donor who has recently died or from a living person, usually a relative. The kidney must be a good match for the patient’s body. The more the new kidney is like the person receiving the kidney, the less likely the immune system is to reject it. The immune system protects a person from disease by attacking anything that is not recognized as a normal part of the body. So the immune system will attack a kidney that appears too “foreign.” The patient will take special drugs to help trick the immune system so it does not reject the transplanted kidney. Unless they are causing infection or high blood pressure, the diseased kidneys are left in place. Kidneys from living, related donors appear to be the best match for success, but kidneys from unrelated people also have a long survival rate. Patients approaching kidney failure should ask their doctor early about starting the process to receive a kidney transplant.

Anatomical diagram of a female figure with a transplanted kidney. The two diseased kidneys are still in place on either side of the spine, just below the rib cage. The transplanted kidney is located on the left side, just above the bladder. A transplanted ureter connects the new kidney to the bladder. Labels point to the diseased kidneys, artery, vein, transplanted kidney, transplanted ureter, and bladder.

Kidney transplantation

Points to Remember

* The kidneys are two vital organs that keep the blood clean and chemically balanced.

* Kidney disease can be detected through a spot check for protein or albumin in the urine and a calculation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) based on a blood test.

* The progression of kidney disease can be slowed, but it cannot always be reversed.

* End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is the total or nearly total and permanent loss of kidney function.

* Dialysis and transplantation can extend the lives of people with kidney failure.

* Diabetes and high blood pressure are the two leading causes of kidney failure.

* People with reduced kidney function should see their doctor regularly. Doctors who specialize in kidney disease are called nephrologists.

* Chronic kidney disease (CKD) increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

* People in the early stages of CKD may be able to save their remaining kidney function for many years by

o controlling their blood glucose

o controlling their blood pressure

o following a low-protein diet

o maintaining healthy levels of cholesterol in the blood

o taking an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)

o not smoking

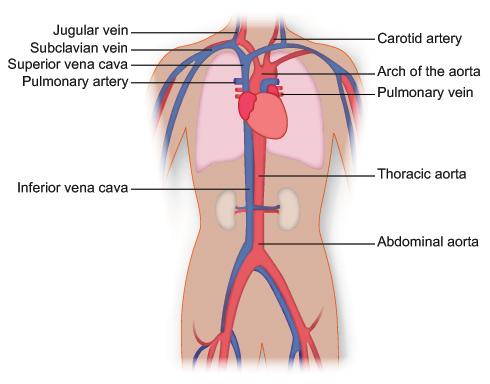

Vasculature of the Torso:

The one-way circulatory system carries blood to all parts of your body. This process of blood flow within your body is called circulation. Arteries carry oxygen-rich blood away from your heart, and veins carry oxygen-poor blood back to your heart.

In pulmonary circulation, though, the roles are switched. It is the pulmonary artery that brings oxygen-poor blood into your lungs and the pulmonary vein that brings oxygen-rich blood back to your heart.

In the diagram, the vessels that carry oxygen-rich blood are colored red, and the vessels that carry oxygen-poor blood are colored blue.

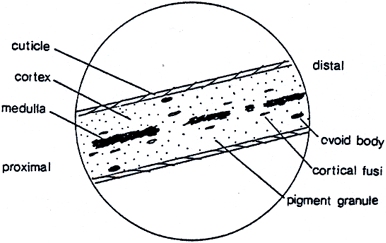

Basic Structure of Hair

Hair can be defined as slender, thread-like outgrowth from follicles (opening in the skin through which a hair grows) in the skin of humans and animals. Composed mainly of keratin, it has three morphological regions - the cuticle, medulla, and cortex.

Cuticle

The cuticle is a translucent outer layer of the hair shaft consisting of scales that cover the shaft. Cuticular scales always point from the proximal or root end of the hair to the distal or tip end of the hair.

There are three basic scale structures that make up the cuticle:

* Coronal (crown-like) - The coronal, or crown-like scale pattern is found in hairs of very fine diameter and resemble a stack of paper cups. Coronal scales are commonly found in the hairs of small rodents and bats but rarely in human hairs.

* Spinous (petal-like) - Spinous or petal-like scales are triangular in shape and protrude from the hair shaft. They are found at the proximal region of mink hairs and on the fur hairs of seals, cats, and some other animals. They are never found in human hairs.

* Imbricate (flattened) - Imbricate or flattened scales type consists of overlapping scales with narrow margins. They are commonly found in human hairs and many animal hairs.

Combinations and variations of these types are possible.

Medulla

The medulla is a central core of cells that may be present in the hair. If it is filled with air, it appears as a black or opaque structure under transmitted light, or as a white structure under reflected light. If it is filled with mounting medium or some other clear substance, the structure appears clear or translucent in transmitted light, or nearly invisible in reflected light. In human hairs, the medulla is generally amorphous in appearance, whereas in animal hairs, its structure is frequently very regular and well defined.

When the medulla is present in human hairs, its structure can be described as fragmentary or trace, discontinuous or broken, or continuous.

Cortex

The cortex is the main body of the hair composed of elongated and fusiform (spindle-shaped) cells. It may contain:

* Cortical Fusi - Air spaces located in the cortex of hairs. They are commonly found near the root of a mature human hair, although they may be present throughout the length of the hair.

* Pigment Granules - Small, dark, and solid structures that are granular in appearance and considerably smaller than cortical fusi. They vary in color, size, and distribution in a single hair. In humans, pigment granules are commonly distributed toward the cuticle, except in red-haired individuals. Animal hairs have the pigment granules commonly distributed toward the medulla.

And/Or

* Ovoid Bodies - Large oval-to-round-shaped structures - Large (larger than pigment granules), solid structures that are spherical to oval in shape, with very regular margins. They are abundant in some cattle and dog hairs as well as in other animal hairs. To varying degrees, they are also found in human hairs.

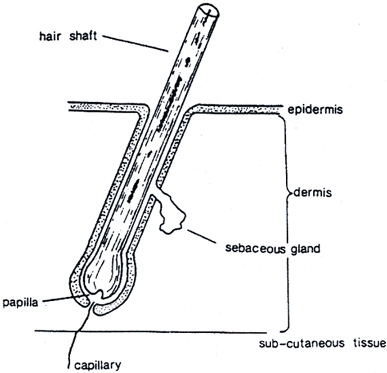

A hair grows from the papilla and with the exception of that point of generation is made up of dead, cornified (horny) cells. It consists of a shaft that projects above the skin, and a root that is imbedded in the skin. The photo below shows how the lower end of the root expands to form the root bulb. Its basic components are keratin (a protein), melanin (a pigment), and trace quantities of metallic elements. These elements are deposited in the hair during its growth and/or absorbed by the hair from an external environment. After a period of growth, the hair remains in the follicle in a resting stage to eventually be sloughed from the body.

Diagram of Hair in Skin